Lockheed Martin, Dynetics, and Raytheon together will produce the US Army Long Range Hypersonic Weapon

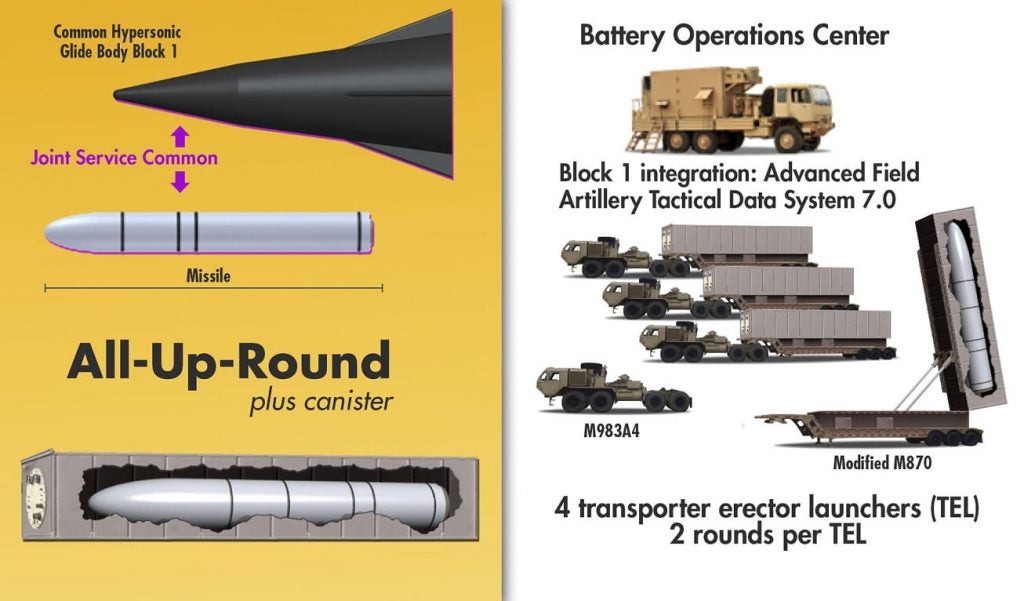

The Army has handed out two large contracts for the development and production of it’s upcoming Long Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW). On August 30th Dynetics was awarded a $352 million contract for the production of 20 Common – Hypersonic Glide Body (C-HGB) prototypes over the course of 3 years. Dynetics have subcontracted Raytheon for the production of flight control systems. Also on August 30th, Lockheed Martin was contracted as the integrator, responsible for all other elements outside the payload. This includes the booster, the mobile launcher derived from Patriot’s launcher, and the fire control system.

Interestingly, Lockheed Martin subcontracted Dynetics for the production of the launcher including hydraulics, outriggers, power generation, and distribution systems. Lockheed Martin’s contract was $347 million with $56 million of that to be awarded to Dynetics on top of the previously mentioned contract. Test flights are expected in 2020 with live fire tests in 2022, with the goal of an operational system by 2023.

As the name suggests C-HGB will serve as a common payload for 3 different hypersonic weapon programs across the branches. These include the USAF’s Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon (HCSW) launched from B-52 as well as the USN’s Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) to be launched from Ohio class SSGNs or even possibly Virginia class vessels equipped with the payload module. Both of these will require significantly more development than the Army’s LRHW who’s developmental predecessor Advanced Hypersonic Weapon (AHW) has already been tested successfully twice, first in 2011 and then in 2017 (the second test was conducted by the USN from the land). In these tests, the glider successfully reached a target some 2,400 miles from the launch point and was able to achieve Mach 8 during the glide phase. The weapon was built by Sandia National Laboratories who launched the glider off a modified Polaris SLBM booster known as STARS.

While the 2,400-mile test is within the range threshold banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty the AHW has a theoretical max range of 3,700 miles keeping it out of the intermediate-range class if only slightly. Unfortunately, during the second longer-range test in 2014, the flight had to be aborted due to a booster failure. However, now that the US has withdrawn from the INF treaty, LRHW is not held to the same limitations. Notably, the LRHW will have a booster significantly smaller than Polaris (34.5 inches in diameter compared to 54 inches for Polaris) putting the weapon firmly into the intermediate-range category.

These “tactical” weapons are a far cry from the strategic ambitions originally driving US hypersonic projects. The Prompt Global Strike program saw the desire for a conventional weapon able to strike any point on the planet from within the US inside of an hour. This began under the Bush administration in the early 2000s and materialized into a collaborative program between DARPA and the USAF known as the Falcon Project. The programs first flying prototype was the HTV-2 glider, which was launched from the Minotaur IV rocket derived from the Peacekeeper ICBM (an absolutely massive platform compared to Polaris). HTV-2 was intended to be tested to 4,400 miles, however, failed during both test flights in 2010 and 2011.

The failure of HTV-2 resulted in the Army’s AHW becoming the primary hypersonic payload across the branches though derivatives of HTV-2 are still being pursued under DARPA’s Tactical Boost Glide (TBG) program. The USAF’s other B-52 launched hypersonic weapon, the Air-launched Rapid Response Weapon (AGM-183A ARRW), will use a glider derived from this with the USN and Army both expected to test the more ambitious glider. TBG based weapons are expected to be more agile but are considered a more risky development path given past failures. The stability of C-HGB brings a great deal of developmental confidence, albeit with performance sacrifices. With $2.6 billion to be spent on hypersonic programs in FY2020 the DoD certainly has no shortage of funds and feels confident in pursuing both approaches.

Even without the failures of the HTV-2, strategic hypersonic weapons were a doomed concept. They were born of an era where the primary fear was a rogue state like North Korea or Iran which could be dealt a serious blow by a handful of these weapons striking key facilities such a nuclear weapon production/storage centers. However, with the transition to peer competition amongst the US, China, and Russia the ability to penetrate missile defense shields to strike key targets such as radar sites and command centers on the tactical level became the priority. There is, of course, the additional fear of using an ICBM launched weapon, that such a launch will be indiscernible from the launch of a nuclear weapon.