Exclusive Interview: Heron Systems’ Vice President Talks AlphaDogfight AI Victory

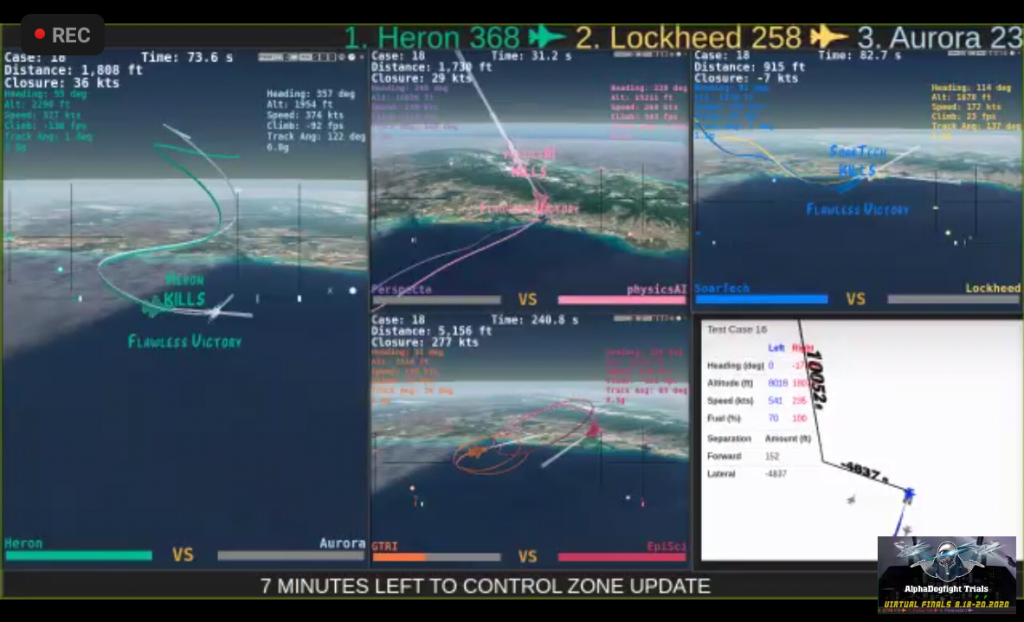

The shock 5-0 victory of Heron Systems’ Falco AI over a human pilot in a simulated F-16 dogfight at DARPA’s AlphaDogfight Trial 3 has resulted in the spilling of much ink. Fighter pilots, computer scientists, academics and tech evangelists alike have all rushed forwards to offer their opinions on what this bodes for the future of air combat, or indeed the future of combat as a whole. Yet outside a live YouTube Q&A hosted from Heron Systems themselves, not much effort has been made to ask Heron Systems for their own perspective.

Overt Defense had the pleasure of speaking with Mr. Brett Darcey, Vice President of Heron Systems and founder and manager of Heron Systems’ Product Development Group, about Falco, AlphaDogfight and where they intend to go next with AI development.

OVD: Could you introduce what Heron Systems does and what projects you are currently working on?

Darcey: We’re a small business, about 30 or so people and we work in defense in the United States. We’re currently working on projects mostly aligned with developing some kind of advanced artificial intelligence or agent-based autonomy for robotic systems and we also do a fair bit of testing and evaluation of airborne systems like communications systems and radars.

OVD: Asides from Falco and AlphaDogfight, what specific AI programmes are you pursuing with regards to the US military? I believe that other news coverage mentioned that Heron was a subcontractor for the AFRL Skyborg program.

Darcey: Yeah, we were, but it’s hard to say that was AI. We did a small risk reduction thing for them, it was helping to test this piece of software that they had and showing that it was working or not working in relevant context. If you go to our website, you can see that we announced we were selected as a prime for DARPA’s Gamebreaker program. And that one’s interesting. We’re using Starcraft II as the simulator, and what we’re trying to do is basically come up with a comprehensive way to assess game balance. And then given that, learn a model for breaking the game or creating ways to fundamentally change the game so that one side is able to comprehensively defeat the other with a high rate of success.

OVD: So, let’s turn to the Falco agent used for AlphaDogfight. Can you explain what sort of architecture was used for Falco?

Darcey: The short answer is we used a lot of them, but the one we ended up going with at the end is called a PPO, or proximal policy optimization. We used that and we did a relatively simple rewards scheme. And we just used a lot of training time to allow the agents to learn the best Basic Fighter Maneuvers (BFM) using that simple reward scheme.

‘The agent we submitted had 31 years of flight training time.’

OVD: So for the training time, I recall the YouTube Q&A mentioning the time figure of five weeks and four billion steps. Are these steps unique scenarios or are they somewhat similar?

Darcey: They are units of time, I think they are hundred millisecond blocks of time within the simulation, so it’s hard to break it down into a number of flights. It netted out that the agent we submitted had 31 years of flight training time in it.

OVD: So how did the Heron team decide on using the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) architecture?

Darcey: Basically trial and error at a very large scale, like informed trial and error. We were not completely naive, we had a plan but we started our original presentation using soft actor critic as the architecture. And what happened is we got through the program and we hit a performance plateau. Through a lot of experimentation, we came to the answer that it was the architecture itself that was holding us back. So we made the switch to PPO and pretty much relaunched the training, but this time with a lot of knowledge of what works and what didn’t, and our hypothesis turned out to be correct.

OVD: What training strategy was used to train the Falco agent?

Darcey: We used a competitive league that was pretty similar to what they used for AlphaStar.

OVD: So when was the decision to change the architecture taken? Was it after one of the trials or before the trials began?

Darcey: It was after one of the trials, probably back in February or March.

OVD: So now that Heron has won the AlphaDogfight trials, how has public response or media coverage been?

Darcey: It’s been overall pretty good. Remember, we’re coming from a profile of having no profile publicly, right? So a lot of it has been “Who are you guys, and what did you do?” But we’ve had some questions, there was a Wired article that was very skeptical of the overall concept and the legal, moral and ethical terms and we’ve had some pushback from there, but generally it’s been pretty positive. I think we tell a good underdog story, so people aren’t really giving us too much grief over it.

‘I think we’ve proven beyond reasonable doubt that you need to take this technology seriously.’

OVD: Are there any particular misconceptions related to Falco or the media coverage that you think are worth addressing?

Darcey: I think the main thing worth addressing is everybody out there who thinks the agent had a great advantage over the human and this was oversold and things like that. The answer to that is absolutely it was, we knew that we were going to have perfect state information and stuff like that. But that wasn’t the point. The point was to show that the technology was ready to be taken seriously. And I would recommend everyone to listen to when the DARPA program manager says what the point of this was, and keep that in mind. There were limits, and the program is what it is, right? This wasn’t a huge program, but we were able to show within the constraints of the program pretty excellent capability, and I think we’ve proven beyond reasonable doubt that you need to take this technology seriously. And it’s ready to be taken seriously by both the defense industry and others who want to do this kind of stuff.

And the other one is, please pay attention. Like we’re not building country killer robots here. And a lot of people jumped to the conclusion that we’re trying to replace the manned fighter and all this. That’s not the point, right? We’re trying to build technologies that augment the human, that make it safer for the human and technologies that can work alongside the human. It’s a very human-focused technology even though it’s an artificial intelligence, and I think people need to pay attention to that, because it was clearly stated by DARPA as what they were going after.

OVD: I think that’s a downside of the broadcasting format used, since they were using an invite-only Zoom system for Days 1 and 2 and only swapped to a public YouTube broadcast on day three. They only broadcast the Day 3 semifinals instead of just the human against AI fight as planned after some complaints that the Zoom meeting link wasn’t working.

Darcey: Remember, the original plan was to do this live in Las Vegas and the virtual thing they had to come up with on the fly. We are working with the Department of Defense, right? So they’re not really used to things like Twitch or Discord servers or YouTube livestreams. So I give them credit just for being as creative as they were.

OVD: Yeah, DARPA actually gave me press access despite registering after the nominal cutoff due to public interest, so I give them a lot of credit as well.

Darcey: We’ve worked with the Air Force, we’ve worked with the Navy, we’ve worked with the Army, we’ve worked with NASA, DARPA is the easiest to work with, and they seem to be the most creative when it comes to this type of stuff, so, you know, full credit to them.

OVD: While we are discussing going from Las Vegas to virtual, how did the COVID-19 outbreak affect the development of Falco for Trial 3?

Darcey: First off, it caused a four month extension to the program, which was unfortunate for us in that at the first Trial 3 date which was going to be in April, we were leading by a lot, and in the intervening months, a few of the other teams, certainly all teams in the semifinals kind of figured out what we had figured out earlier in the program. So they caught up and we were stuck in a performance plateau. So competitively everyone caught up to us and then we kind of accelerated away a little bit at the end. But if we held the trial in July or June, I don’t know if we would have won, it would have been close, certainly closer than it was. From a technology perspective, it did allow us to explore a lot more of the ideas and allowed us to more fully implement a lot more of the ideas that seemed to be promising. So at the end, the agent you saw on the livestream was significantly more capable than the agent that would have been shown in April.

OVD: So it’s definitely a mixed blessing?

Darcey: Yeah. Also, the event in April was going to be closed with lots of VIPs, and this one was open with a much broader reach. So, it remains to be seen which would have been better for us, right? But I was glad that a lot more of the people that I know who don’t really know what I do were able to get a glimpse into our world, so that was a very personally gratifying thing. So now my kid can say “Oh, I saw what daddy does with his robots” and normally I can’t really communicate to her what I’m doing, so it was very, very nice for that.

OVD: On Falco’s advantage over rival agents, I think we can say that Falco’s “signature move” was its high aspect shots, how did that come about?

Darcey: The agents figured that out themselves. Like I said, we used a very simple reward scheme that was effectively “what is your track angle to your target” and “what is your distance to target” and some other things built off of that. But those are the basics, and we never told it to shoot on the merge like that. What we think happened is during training, engaging in traditional Basic Fighter Maneuvers (BFM) started to result in a lot of draws, wherein the agents all learned how to conduct BFM to a point where it was hard to get a tracking shot on them. And so the more successful agents that bubbled up with high win rates figured out an alternative tactic where they could start the engagement with that head on shot and look to further create those opportunities if the adversary didn’t cooperate. And that’s where it came from, and it’s a competitive league so we picked the winners, and the winners were those agents. Interestingly, though, you saw in some of the fights against Lockheed Martin (another competing AI agent) and Banger (the human F-16 pilot) that when they declined to do the head on merge and got into a two circle thing, we were able to do successful BFM and get behind and get the shot. So that was the move that won the competition, but that wasn’t what we told it to do. And I think that’s an important distinction, we didn’t hand program that behavior.

‘We were able to do successful Basic Fighter Maneuvers and get behind and get the shot.’

OVD: So it basically came about due to how Heron trained Falco for smoothness of controls?

Darcey: The first thing we tried to get was expert handling of the aircraft, because if you don’t handle the aircraft expertly, you cannot conduct or capitalize on opportunities to their fullest extent. The analogy we used internally was a basketball game. “You can have all the idea in the world that you want to drive to the lane and finish with your right hand, but if you don’t have the body control, don’t have the athleticism to get up to the rim, you’re not going to be able to pull it off.” So we didn’t want to have agents that knew what to do but couldn’t execute it. We’d rather have agents that could execute every opportunity that was available, and then teach them to recognize those opportunities.

OVD: I read on the Heron Twitter page that Falco was named after the Star Fox character. How did Heron settle on that name?

Darcey: This goes back to when we were pitching ourselves as a competitor to DARPA, and we wanted to have an interesting title, right? You don’t want to be like “Heron Systems can build an AI agent for you!” We went with “Project This”, whatever that name is. So we were thinking, these are thought of as a wingman or loyal wingman, being out there helping the human. So we said “Okay, in the world of video games, where are there examples of really good wingmen or helpers?” And then, if we can, keep it in the context of aerial combat and under no circumstances are we going to go with a Top Gun reference. We pretty quickly actually said “Well, Star Fox had a bunch of wingmen that helped you out”, so we went through them and we have Peppy, we have Falco and we said “well, Falco is the only one that was usually pretty helpful and somewhat trustworthy”. We said that Peppy was a bit of a joke and I don’t remember the other characters’ names, but Falco was the one was stood out, like “yeah, that one’s pretty good, you can take that one into combat, it won’t completely embarrass itself.” So that’s what we went with.

OVD: Well, after seeing what Falco did, I was wondering if Heron was going for something like Pixy for the head on charging attacks.

Darcey: Remember, we didn’t know ahead of time that that was the behavior that would emerge. So when we set the name, it was just trying to be fun.

OVD: So what other names were considered but ultimately lost out to Falco?

Darcey: Good question, I don’t know if I can remember any offhand, but we generally considered sidekicks. Like how Batman has Robin, or Sonic the Hedgehog has a helper whose name currently escapes me. Ultimately, Star Fox was so close to air to air combat, so we pretty quickly settled on that.

‘We need to be able to anticipate and interpret human actions better.’

OVD: The talks from the DARPA people emphasized “human-machine symbiosis”. What do you think Falco needs to be able to pull that off?

Darcey: First and foremost, Falco right now has no way of accepting any input from a human or from anyone really, it’s a completely autonomous system. So one of the things we’re looking at going forwards is investigating how do we build these types of AIs to not only work with humans, but to anticipate human behaviors and actions, so that when the human does something unexpected to the AI, it doesn’t completely fall apart. It needs to be robust to human decision making that may consider outside elements that the agent may not. For example, with Falco right now, those head on passes and high aspect merges, a human’s not going to do that. And if we put Falco in a 2v2 combat scenario and it expected its wingman to do that and he doesn’t, then Falco is going to have a problem. It’s not going to respond very well to that. So we need to be able to anticipate and interpret human actions better. There’s some techniques based on imitation learning and things like that that can help there, but there’s a lot of work that needs to be done. And we need to have some kind of communications and command and control approach that allows for that symbiosis to not be an overwhelming burden on humans. If you talk to the Dota 2 guys who played with the OpenAI Dota bot, after they were done, they said they felt like they were solving a puzzle because they had to figure out what the AI was trying to get them to do. And that’s not where you want to be, the human can’t be in a position where it can’t fully trust and understand what the AI is going to do and why it’s doing it. Pushing on those fronts is really necessary if you want to talk about any kind of human-machine teaming or symbiosis.

‘This is going to be a long process, but the basic idea is get it up in the air, prove that it can work.’

OVD: So I understand the next step for Falco is the sim-to-real process, which would involve mounting it in a small UAV. I’m having trouble visualizing the sort of UAV being used, would you have any reference for what sort of UAV Heron will be placing Falco in?

Darcey: We are talking about a small fixed wing, kind of delta wing type UAV with maybe a two or three foot wingspan, something commercially available and cheap because we are going to crash them. Our background in robotics is doing things for real and doing it under low size, weight and power constraints, so naturally when we do the sim to real question, we’re going to head there first. It’s a cost thing, but it’s also familiarity with their aircraft themselves. And our first steps will be simply providing in a virtual way to the aircraft an idea of where its opponent is right now. We’re not going to put a radar system on board and make it find stuff, we’re going to provide the same state space we had with Falco, and literally just test. Can it maintain control of the drone, does the flight control system allow it to work in real life the way it works in the simulation. And then as we get more confident there, we can start to change the state space and the observation space to get more real. This is going to be a long process, but the basic idea is get it up in the air, prove that it can work and then start to relax the constraints. Figure out where it breaks, improve it and then keep going.

OVD: After AlphaDogfight, are there any other DARPA programs that Heron is interested in or actively pursuing entry into?

Darcey: That’s a pretty general statement, but yes, we’re always looking at DARPA programs because they do really interesting work and they have an agency history of investing in the little guy high risk entrant who can deliver gamebreaking capability. So that’s a good spot for us as we try to grow our operations a little bit and become more of an established player. As to specifics, we did apply for the follow on work for the DARPA Air Combat Evolution (ACE) program, nothing to report there. We hope to have something to announce in the near future, but right now we’re just in a waiting game. There’s always other stuff, but I don’t know if we have anything DARPA specific on tap, other than waiting to hear about ACE.

OVD: I was looking at the DARPA Gunslinger spec, and the concept of a missile with a gun in it seems perfect for Falco.

Darcey: That’s true, but it’s a question of bandwidth too. We’re taking lots of incoming, I’m literally standing outside of the offices of a major defense contractor right now, having just taken a break from a morning’s worth of meetings talking about what we could do with them. So there’s a lot of incoming from industry and then some from the government side, but the program timelines are long enough that whatever programs are out there right now have been in place for some time. Going forwards though, we’re going to see where this AI, this approach to building the AI really can be used and I’m sure there will be lots and lots of opportunity.

OVD: The Q&A mentioned that your servers use Nvidia GTX 6000s. Is Heron looking forward to the Ampere GPUs or has an order already been placed for some?

Darcey: Buying compute for us is a tough thing because it’s expensive. We haven’t really thought through what our next requirements are going to be. The ADT servers are going to be available to be used for whatever we take on next, so we’ll probably keep using what we have. What we’re interested in doing, though, is trying to work with Nvidia to be a partner of theirs, so that we can bring that price point down a little bit and leverage some of that first rate technology. The interesting thing there though, we did demonstrate that you can use Nvidia’s commercially available stuff to really, really good effect and you don’t have to always go straight to putting everything up in the cloud and use AWS or Google’s cloud to do the training. You can build an in-house stack at a price point that isn’t cheap, but not crazy and get it done. We’ll certainly keep using Nvidia’s products, we really like them and we will grow organically as the work demands it.

OVD: One last question, has Heron figured out what to do with Colonel Javorsek’s helmet?

Darcey: We actually are going to get it on Thursday, and we know what we want to do with it, we just haven’t ordered the podium and the acrylic case because we weren’t sure what the exact sizing is. We have two virtual reality cockpits set up for our own stuff like helping training these agents. It’s a prominent part of our office and we’re going to put Animal’s helmet right there in the middle between the two cockpits so that whenever you’re in the cockpit dogfighting, you know that Animal is kind of watching, right? He was the one who took a bet on us and allowed us to get to where we are right now. We need to be mindful of the fact that he really was very encouraging and very helpful, and his standards live up to you, right? He was an F-22 test pilot, like that guy’s world class. So we need to be world class in return.

While much work remains to be done for Falco to fulfill what DARPA intends to achieve with the Air Combat Evolution, its performance in AlphaDogfight Trial 3 certainly is cause for optimism. Overt Defense would like to thank Mr. Darcey for giving us Heron Systems’ own perspective on what the future holds for Falco.