Editorial: China’s Shifting Stance on Ukraine

Initially, China’s attitude towards the invasion of Ukraine could best be described as tacit consent. While Beijing had maintained a neutral diplomatic stance abroad since the start of the invasion, it had refused to condemn Russia and it is likely that China and Russia had been consulting each other ahead of the invasion with the New York Times stating that American officials had shared reports of China requesting Russia postpone its invasion until after the Winter Olympics hosted in China. Interestingly, both the 2008 invasion of Georgia and 2014 attack on the Crimea were carried out while Olympics were ongoing (Beijing 2008; Sochi 2014). Some sources have also reported that the US government unsuccessfully sought Beijing’s support in trying to dissuade Putin from moving forward with his invasion.

Yet while China tried to present a neutral posture abroad, the same could not be said about Chinese actions aimed at their own nationals. Other countries evacuated their citizens before the invasion but China did not. Once the invasion begun, the Chinese embassy in Kyiv instead told citizens to remain in place and proudly display Chinese flags from cars and windows; it was likely anticipated that Russian troops would overrun Ukraine in days and offer protection to Chinese citizens.

Similarly, while the government made no official statements, the censorship apparatus went to great lengths to censor and punish those who would make statements in support of Ukraine. With 13.6 million followers, Chinese talk show host Jin Xing had her account suspended for calling for peace in Ukraine. A letter from five prominent Chinese scholars was also quickly suppressed by Chinese authorities. Posts which showed active support for Russia, or expressed interest in taking in “homeless young Ukrainian women” or “Ukrainian beauties”, were initially allowed to stay up. Even Chinese citizens voicing their desperation and calling for help from within Ukraine were censored by China.

However, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) soon realized that things were not exactly going as they had expected. After the first one-hundred hours, Russian troops had failed to take Kyiv or any other major Ukrainian city. With each passing day, Russian incompetence was becoming apparent at almost every level: strategy, tactics, logistics, intelligence and operational security. As Ukrainian media picked up on the response on Chinese social media, particularly that which contemplated exploiting young Ukrainian women, Chinese citizens began to report that they are being barred from access to supplies and shelter and being forced to pretend to be Japanese to avoid persecution. The Chinese embassy in Kyiv quickly reversed its stance and advised Chinese nationals to conceal their status as citizens of China. In Beijing, the censorship apparatus now began to suppress both pro-Russian and anti-Russian posts with any references to “Ukrainian beauties” soon disappearing off the Chinese internet. However, it seems that the Chinese public is still mostly taking a pro-Russian stance.

Moreover, China was likely surprised by how powerful and unified the Western response was. The cracks within Europe, and between Europe and America, seemingly disappeared overnight while the entire democratic world committed itself to enforcing the most extreme sanctions in decades. Finland and Sweden were pushed closer to NATO, defense budgets are rising from Australia to Germany, while citizens all over the world expressed largely unanimous support for Ukraine. This all means that if China was perceived as actively supporting Russia’s invasion, the PRC could face the anger of a unified Western world. Chinese companies would soon face economic backlash for aiding Russia while already-deteriorating perception of China in the democratic world could quickly solidify and take a more concrete form.

Particularly important is the fact that Japan had taken such a strong stance against Russia. The island nation had long resisted antagonizing Moscow due to the hope that the long-standing dispute over the Kuril Islands could be resolved diplomatically. However, not only has Japan fully joined Western sanctions, it has also taken the unprecedented step of sending defensive supplies such as helmets, camouflage and medical supplies to Ukraine. Australia and Taiwan have also shown strong solidarity with the Ukrainians. Moreover, South Korea’s 9 March elections resulted in Yoon Suk-yeol from the People’s Power Party narrowly beating Lee Jae-myung of the currently ruling Democratic Party of Korea. Yoon has been very vocal in his opposition to China, often using rhetoric such as calling Covid-19 the “Wuhan” virus, and had long called for South Korea to drop its strategic ambiguity and to instead align more closely with America. The resulting situation in the Indo-Pacific is one in which China is more likely to face a unified response from not just outside but also within the region.

Therefore, despite Putin now calling for Chinese military aid, it is unlikely that Beijing will be particularly willing to provide significant help to Russia. The US has already warned China of repercussions for doing so and it seems Russia is already on an accelerated track to becoming reliant on China for its survival. Perhaps China will covertly supply some limited aid in hopes of keeping Western attention pinned to Europe or in hopes of seeing Russia bleed longer and thus become more dependent on the PRC but any major support is extremely unlikely.

Renewed attempts have been made this week to reiterate to the world that China has nothing to do with Putin’s invasion and even to show support to Ukraine. China’s ambassador to the US released a statement via the Washington Post on 15 March in which he denied assertions of Chinese “tacit consent” or support for Russia and said that the UN Charter must be upheld. The ambassador criticized threats made against Chinese companies, denied that China was planning to invade Taiwan and highlighted China’s efforts to promote peace talks and humanitarian causes. Qin Gang said in the opinion piece:

“China is the biggest trading partner of both Russia and Ukraine, and the largest importer of crude oil and natural gas in the world. Conflict between Russia and Ukraine does no good for China. Had China known about the imminent crisis, we would have tried our best to prevent it. […] China is committed to an independent foreign policy of peace. As a staunch champion of justice, China decides its position on the basis of the merits of the issue. On Ukraine, China’s position is objective and impartial: The purposes and principles of the U.N. Charter must be fully observed; the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries, including Ukraine, must be respected; the legitimate security concerns of all countries must be taken seriously; and all efforts that are conducive to the peaceful settlement of the crisis must be supported.”

While not a direct condemnation of Russia, the use of the word “respecting” when describing the need to uphold Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity has more weight than the words “taking seriously” in the context of Russian security concerns. Qin Gang also appeared on CBS’ Face The Nation stating that China is sending food and medicine to Ukraine, “not weapons and ammunition to any party, we are against a war.” Similarly, Chinese State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi said on 19 March, that “we have always stood for maintaining peace and opposing war. This is not only embedded in China’s history and culture, but also the foreign policy China has always committed to,”

A strong stance was also taken by China’s ambassador to Ukraine, Fan Xianrong, who praised the resilience of the Ukrainian people and said that China “would never attack Ukraine” saying:

“I, as an ambassador, can say with responsibility that China will always be a force for good for Ukraine in the economic and in the political sense. […] We will always respect your state, will develop relations on the basis of equality and mutual benefit. We will respect the path chosen by Ukrainians because this is the sovereign right of every nation.”

China’s Foreign Ministry initially refused to comment. However, on Thursday, foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian gave full support for Xianrong’s position.

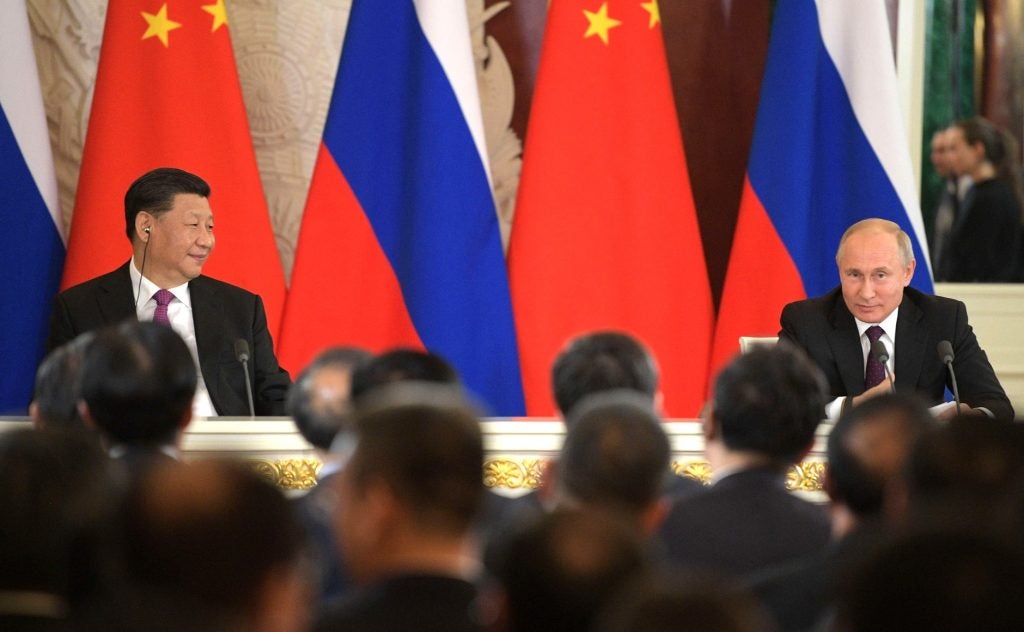

Friday, 18 March, saw a nearly hour-long phone call between Xi Jinping and President Joe Biden on the issue of Ukraine. The call was described as constructive but the White House’s official statement which followed the call was very short and lacked much substance or detail.

It is likely that China did cooperate with Russia to some extent before the invasion as the initial orders to Chinese citizens in Ukraine betray although it may be worth asking how much ability did China have to dissuade Putin from launching his war. However, with the war going poorly for Putin and the CCP fearing a major backlash from a democratic world which is more united than ever, China has been trying to distance itself from Russia. Nevertheless, a clear picture of the exact state of ongoing Sino-Russian cooperation remains elusive and the PRC has continued to refuse to condemn Russia’s invasion or join sanctions. It should also be noted that the intended audience for China’s anti-war statements is not the Chinese people or Russia but rather the West.

For the latest on the war in Ukraine, check out our daily updates.

The opinions expressed in this editorial are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of Overt Defense