From Stability to Asymmetry: The Ukrainian Navy

With a coastline of 2,759 km and an exclusive economic zone of more than 72,000 km², Ukraine is a state whose military and economic national interests are closely linked to the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. Therefore, having and maintaining a modern and developed navy with maritime mobility is one of the issues of critical importance for Ukraine from the past to the present. Establishing the Ukrainian Navy, in the wake of the dissolution of the USSR in December 1991, has been one of Kyiv’s most challenging tests. This problematic process continues today with the efforts to resurrect the naval forces from the ashes of the naval forces that have almost disappeared in the face of the Russian threat since 2014.

From Soviet Shadow to Sovereign Seas: The Establishment and Early Years of the Ukrainian Navy

The 15 successor republics established after the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) have had some disagreements over sharing the Bolshevik legacy. However, the most protracted dispute among these new states was undoubtedly between the Russian Federation and Ukraine, which sought to extract as many political, economic and military gains as possible from the wreckage of the USSR and, at the same time, gain the role of “big brother” over the newly independent state. Although there were many areas of conflict in the bilateral relations between Moscow and Kyiv, the most important were the division of the Soviet Black Sea fleet, the status of the Russian base in Sevastopol and the sovereignty of the Crimean peninsula.

Negotiations between the parties began in 1992 and were concluded in May 1997 following a meeting between Ukrainian Prime Minister Pavlo Lazerenko and his Russian counterpart Victor Chernomyrdin. According to this agreement, the Black Sea Fleet of the USSR Navy, which had been under the joint command of Russia and Ukraine for five years, was divided in half between the parties. However, according to the terms of the agreement, Ukraine transferred 32% of the 50% allocated to it to the Russian Federation for $521.060 million while retaining the remaining 18% [43 warships, 132 ships and patrol boats, 12 aircraft, 30 helicopters, other equipment and military supplies].

However, while disbanding the Black Sea Fleet of the USSR, Ukraine’s share of ships was in deplorable condition, and some of them were deliberately rendered unusable by Russia. Between 1997 and 2004, Ukraine sold or decommissioned 40 per cent of its existing warships and boats and 50 per cent of its auxiliary vessels due to the end of their service life and loss of tactical and technical characteristics. Between 2004 and 2013, 24 warships and boats were withdrawn from the Navy for similar reasons. In addition, during this period, many remaining major projects, such as the Project 1164 Slava Class Admiral Lobov Guided Missile Cruiser and the Project 1143.7 Class Ulyanovsk Nuclear Propelled Heavy Aircraft Carrier Cruiser, which were initiated just before the collapse of the Soviet Union and whose construction was over 70 per cent complete, were sold by the governments of the time because they were “contrary to the defence doctrines” of the country and costly.

Ukraine has developed several programmes to compensate for these naval losses, including constructing and acquiring new ships and boats and modernising existing corvettes, minesweepers and missile boats. However, most of the naval development programmes were hampered by budgetary problems. In its first decade, the Ukrainian Navy was able to add only one Grisha V class Ternopil (U209) Small Anti-Submarine Warfare Ship to its fleet, built by Kuznia na Rybalskomu shipyard.

Fresh Challenges: 2014 Annexation of Crimea and Reconstruction Strategies

The Ukrainian Navy, which could not undergo a successful reform process during the immediate post-Soviet period due to economic crises and corruption in the country. More over the navy lost 75% of its personnel, 70% of its ships and a large part of its naval power, including its basic infrastructure, when the Russian Federation annexed Crimea in 2014. These losses included important vessels such as Ukraine’s only submarine, Project 641 (Foxtrot) class U01 Zaporizhia and Project 775 (Rapucha) class U402 Konstantin Olshanski LSD. At the same time, the fleet’s flagship F-130 Hetman Sahaidachny frigate and around ten warships and support vessels were not captured. In April, May and June 2014, Russia returned to Ukraine some 35 ships it had seized following the illegal referendum on 16 March. However, the return of many ships, which were in better condition and more advanced than the others, needed to be authorised, citing the conflict in the Donbas. Of the ships that could not be returned, the useful ones were later incorporated into the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

The Ukrainian naval forces, which were on the verge of extinction after the annexation, have started intensive and painstaking work to restore and improve the Navy’s capabilities and to harmonise them with the current threats from the Russian Federation. In particular, the Ukrainian Navy has launched a new strategy to restart projects to build multipurpose corvettes and anti-ship missile systems and small artillery armoured boats, which had been frozen by previous state and armed forces administrations, with the aim to build a “Mosquito fleet rapidly”.

Within the framework of these initiatives, which are mainly focused on acquiring effective, small and inexpensive floating platforms to protect Ukraine’s national interests in the Black Sea and Azov basin, Kyiv soon began construction of a series of Project 58155 Gyurza-M class small armoured artillery boats and Project 58181 Centaur class fast attack craft. At the same time, the Luch Design Bureau in Kyiv unveiled for the first time the country’s first domestic anti-ship missile, the R-360 Neptune, despite the poor state of the arms industry and lack of experience. In addition, the United States decided to donate five Island-class patrol boats to Ukraine under the Excess Defence Articles (EDA) and approved the sale of 16 Mk VI patrol boats through the foreign military sales channel in support of the Kyiv government’s attempts to restore its naval capabilities.

Towards the end of 2018, Ukraine developed the “Naval Strategy of the Armed Forces of Ukraine 2035” programme for the creation of a balanced fleet, including more advanced floating platforms, as well as a more modest “mosquito fleet” concept focusing on small, fast and inexpensive platforms on the Path to Building a NATO-Compatible Navy. This study consists of an introduction and five main chapters, including the mission, vision and values of the country’s naval forces. The first chapter details the mission, vision and values of the Ukrainian Navy. The second chapter analyses the strategic factors affecting the future of the Ukrainian Navy. The third chapter emphasises the naval capabilities required for the construction of modern naval forces. The fourth section describes the roadmap to be followed during the implementation phase, while the fifth and final section provides an overall assessment of this document.

Ukraine took the first significant step under the 2035 Naval Strategy programme by signing a military cooperation agreement with Turkey in 2020, which includes intentions to initiate and implement joint projects for the construction of warships, uncrewed aerial vehicles and all types of turbine engines. Under the terms of the agreement, Turkey will build four Ada-class corvettes for Ukraine, two of which are definite and two of which are optional. The construction of Ukraine’s first Ada-class corvette ‘Hetman Ivan Mazepa’ started on 07 September 2021 and was launched on 02 October 2022 in Istanbul. The ship is currently undergoing sea trials in Turkey, and it remains unclear when it will be delivered to Ukraine due to the current war situation. In addition, Ukraine’s second island-class corvette, “Hetman Ivan Vyhovskyi”, whose keel was laid on 18 August 2023 and launched on 01 August 2024, is expected to be ready for service by 2025.

Apart from this acquisition, Ukraine has not taken a major step forward in the 2035 Naval Strategy programme in the face of the large-scale Russian invasion that started in 2022 and is still ongoing. However, in the meantime, the Navy has made minor improvements to the “Mosquito fleet”, such as the supply of small arms and optical equipment, and has had the opportunity to learn better how to plan and conduct naval operations by participating in major naval exercises such as Sea Breeze.

2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine: A Rematch of the Battle of the Black Sea

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched a large-scale invasion against its neighbour Ukraine. In a conflict shaped predominantly by ground troops since the early days of the war, with Russia gaining the upper hand on the front line, Ukraine achieved extraordinary success in the Black Sea, which surprised many observers. Without an operational navy from the beginning of the conflict and with only a modest number of small patrol boats, Ukraine managed to destroy 26 warships of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, forcing them to retreat to a safer harbour hundreds of miles from Crimea. The Ukrainian Navy’s successes in the Black Sea were made possible by the combined and effective use of cruise missiles from Western partners, R-360 Neptune anti-ship missiles developed by the Luch Design Bureau in Kyiv, bomb-laden unmanned ships and drone systems. The Ukrainian Navy (alongside the SBU) operate a flotilla of fofferent unmannd naval drones including the Magura and ‘Sea Baby’ which have been used to harass and effectively engage larger Russian naval assets.

Russia’s inability to support its Black Sea fleet due to the blocking of the passage of Russian warships stationed in the Mediterranean through the Dardanelles and Istanbul straits under Articles 19, 20 and 21 of the Montreux Convention, which Turkey decided to implement on 28 February 2022, has provided a significant boost to Ukraine’s continued success in the Black Sea.

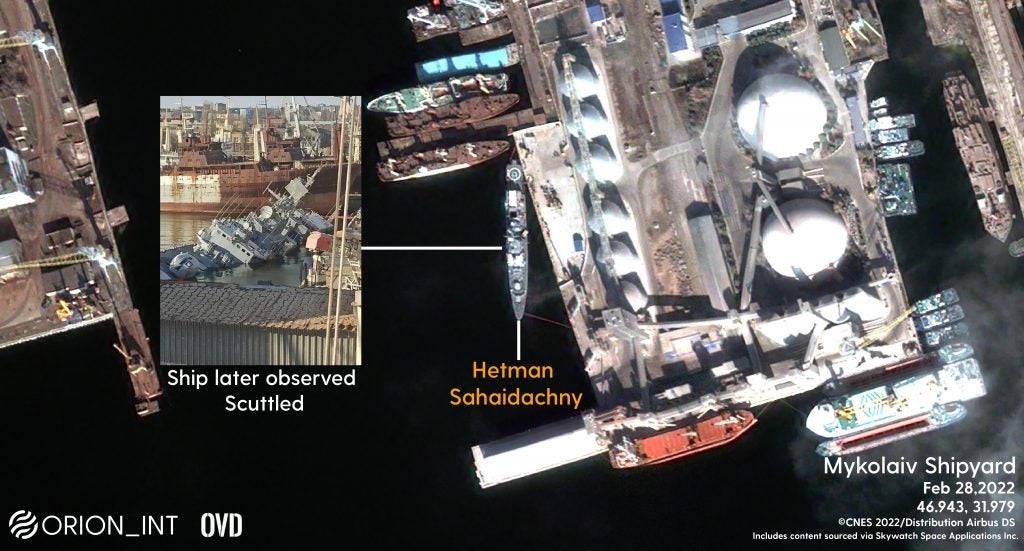

Although the Ukrainian Navy achieved significant victories during this period, it also suffered some losses. According to the Netherlands-based Oryx website, which monitors military losses based on visual evidence and open-source intelligence, the Ukrainian Navy’s losses include 41 surface vessels. Of these, 14 are classified as destroyed, eight as damaged and 19 as captured by Russia. This included the Krivak III-class frigate, ‘Hetman Sahaydachniy’, once Ukraine’s flagship, which was scuttled early in the war. However, considering that most of the naval platforms lost are patrol boats, Ukraine’s losses are pretty small and insignificant compared to the losses of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Moreover, these gaps in Ukraine’s Navy are being rapidly closed by the military support it receives from its Western allies, such as patrol and combat boats, high-speed boats and unmanned underwater vehicles, and there has been no decline in its operational capability in the Black Sea.

Since the beginning of the war, the floating platforms that the allies have contributed or committed to contribute for the Ukrainian Navy and naval guards are as follows:

- Australia: Sentinel 830R RHIBs.

- Belgium: Three Tripartite-class minehunters.

- Canada: Ten multipurpose boats.

- Denmark: Unmanned water vehicles.

- Estonia: Two Roland-class patrol boats.

- Germany: Ten autonomous naval boats.

- Netherlands: Two Alkmaar-class minehunters, thirty-one RHIB/FRIS and three CB90 gunboats

- United States of America: Ten Dauntless Sea Ark patrol boats, two Small Unit River Craft (SURC), six 40-metre river patrol boats, uncrewed coastal defence vessels (USV) and forty armoured river boats.

- United Kingdom: twenty-three Offshore Raiding Crafts, two Sandown class minehunters and fifty small military boats.

- Sweden: Underwater vehicles, ten CB90 gunboats, twenty patrol boats and nine jet skis.

- Portugal: Three high-speed boats.

- Finland: indefinite number and model of armoured gunboats

While some of this international support has reached Ukraine, the vast majority still needs to be delivered. Some undelivered surface platforms are due to donor countries’ recent announcement of commitments; others will reach Ukraine in the coming years after undergoing maintenance and modernisation prior to delivery. In addition, the two Sandown class minehunters donated by the United Kingdom are ready for delivery but cannot enter the Black Sea due to the Montreux Convention, which Turkey honours. Therefore, these ships will only be able to reach Ukraine when the conflict ends.

What Happens Now?

Ukraine’s success at sea will not be decisive in a predominantly land-based war, except to boost the army’s morale and help it sustain its battered economy by reopening the Black Sea trade routes. Knowing this, the Ukrainian authorities are prioritising procuring other military equipment urgently needed by the army, such as air defence systems, cruise missiles, artillery, tanks and armored vehicles, rather than fulfilling the obligations of the current “2035 Naval Strategy programme”. Moreover, the fact that Kyiv is satisfied with the feedback it has received so far from the simple, low-cost, bold, innovative and asymmetric approach it has adopted in the Black Sea War is an indication that it will take steps to continue this concept in the near term. In addition, for the above and similar reasons, it would not be wrong to conclude that the current war must end for Ukraine to build a balanced navy that includes more advanced floating platforms instead of a “mosquito fleet” consisting of patrol boats, a few mine hunters and unmanned naval vehicles.